Chennai, then Madras, 1819. Syed Mir Mohsin Husain, a jeweller from Arcot, was working in the store of his employer, George Gordon, when some British military officials stopped by with a strange instrument, asking if Mohsin could fix it. Though he had never seen such an instrument before, he managed to repair it, a skill noted by one of these officers, Lieutenant-Colonel Valentine Blacker, “who was thoroughly impressed with Mohsin’s ‘uncommon intelligence and acuteness’”, states a new book titled India in Triangles: The incredible story of how India was mapped and the Himalayasmeasured by Shruthi Rao and Meera Iyer, published by Puffin, an imprint of Penguin Random House India. From then on, Blacker often turned to Mohsin for help, even appointing him as an instrument maker at the Surveyor General’s office when he (Blacker) became the Surveyor-General of India in 1823.

Meera loves the story of Mohsin, this small-town jeweller, who went on to become an instrument maker and played a crucial role in the Great Trigonometric Survey (GTS), “the most advanced survey of its kind in the Indian subcontinent at the time-and the largest in the world,” as India in Triangles puts it. “I wish more people knew about Mohsin,” says the Bengaluru-based writer and researcher, the convenor of the Bengaluru Chapter of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH).

Shruthi Rao

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

There are other, equally compelling personalities in the book, which tells the story of how the Indian subcontinent was mapped. These include William Lambton, who kick-started the ambitious project; his successors, George Everest, Andrew Scott Waugh and James Walker; scores of mostly unnamed Indian flagmen or khalasis; and Radhanath Sikdar, the Indian mathematician and social reformer who would go on to calculate the height of Mount Everest in 1852.

However, India in Triangles is also about mathematical principles, instruments, and the methodology used to survey this vast land with its complex topography. Additionally, it discusses its major outcomes — including improved maps, a deeper understanding of the Earth’s curvature, and confirmation that Mount Everest is the world’s tallest mountain — and is packed with engaging exercises, trivia, anecdotes, and facts. Shruthi reveals one of them: “There is no evidence that Everest ever saw the mountain named after him,” she says, pointing out that it was actually named by Waugh in honour of his superior. While Everest, unlike his more easy-going predecessor Lambton, appears to have been a bit of a curmudgeon, he was also a “pretty impressive guy. He brought in multiple innovations and made the survey faster,” says the California-based children’s writer and editor.

Meera Iyer

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The start of a survey

The pilot for this great survey was conducted in Banaswadi, Bengaluru, in 1800, merely a year after the defeat of Tipu Sultan in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War. Lambton, who was part of the British regiment that fought this war, had proposed this survey for two broad reasons, explains Meera. The first was that the East India Company, which was rapidly acquiring new territories, needed maps. “Yes, they had maps already, but these were not very accurate,” she says.

Additionally, the geographer in Lambton sought to measure the Earth’s true shape, fulfilling his long-held desire to contribute to the field of geodesy. “In the 1780s, they had started trigonometrical surveys in England, and Lambton was following it very closely,” says Meera. Once Tipu Sultan was defeated, they had access to the entire territory of Mysore as well, which meant that “practically all of South India is no longer enemy territory for the British so they could go almost anywhere they wanted,” she adds. “This idea, Lambton had of drawing a line across the land, could be done. So that is how everything came together.”

William Lambton

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

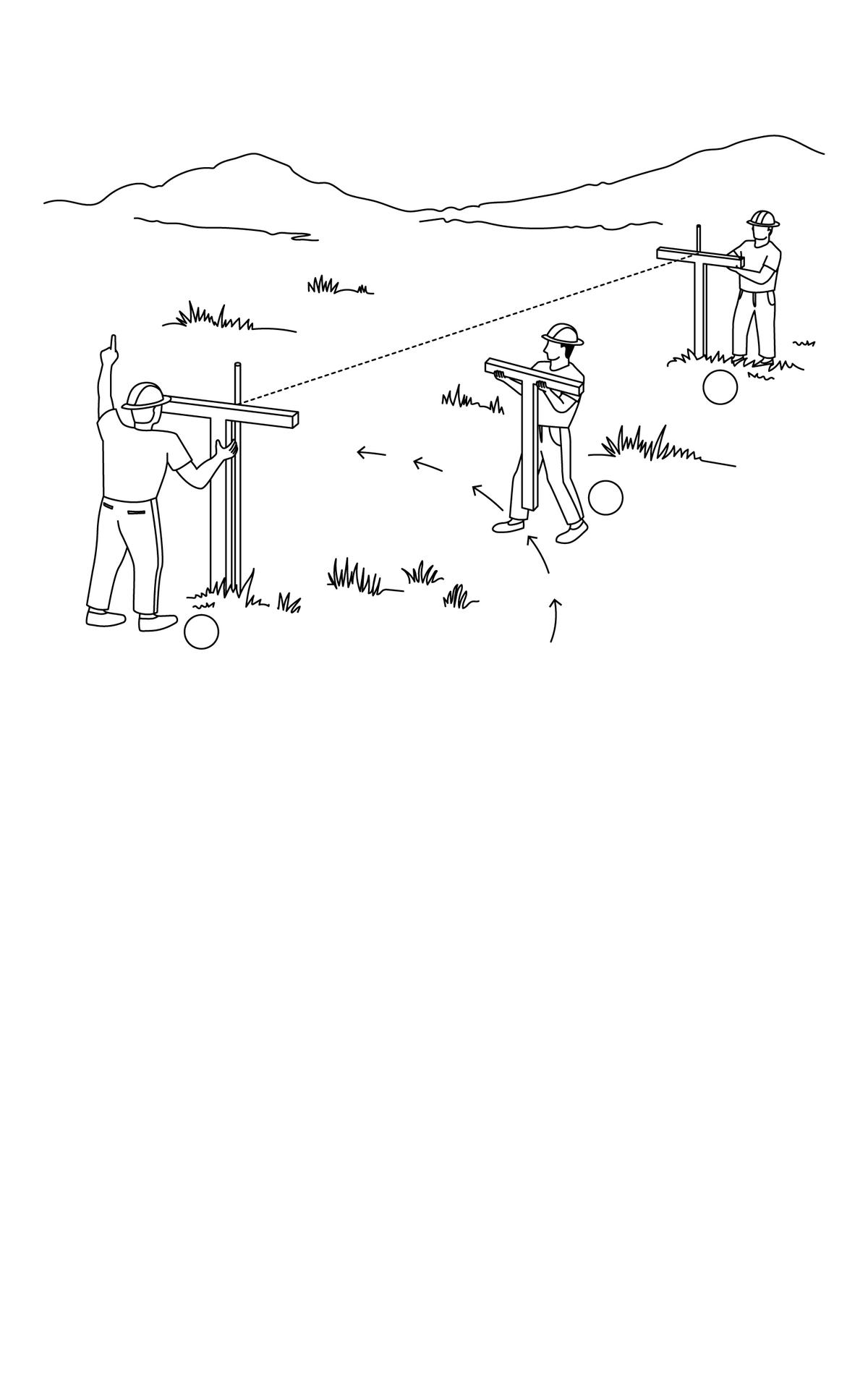

The GTS was based on the principle of triangulation, a process that divides a shape or surface into multiple triangles. “In trigonometry, when you know the measurement of one side and two angles, you can calculate the lengths of the other two sides,” says Shruthi. Using this basic idea, “they were able to draw imaginary triangles across the land.”

According to her, only the first line of the triangle —the baseline —was physically drawn and measured on the ground. “Then, from each end point of that line, they were able to sight the third point of the triangle, measure the angles and find the length of the other two sides of the triangle,” she explains, elaborating that one of these would then become the next baseline, which in turn would be used to map another triangle, and so on. “It became a network of triangles across India, and using these triangles and paper and pencil, they were able to map the entire country.”

A lasting legacy

An illustration from the book depicting how the baseline is measured

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The actual process was arduous, involving the physical labour of lugging heavy equipment through harsh, often hostile terrain, while constantly battling the elements. “They expected it to take around five years,” says Meera, with a laugh. In reality, however, it took nearly a hundred years, with the Great Trigonometric Survey officially kickstarting in April 1802 in Madras two years after the pilot in Bangalore. “He chose the Madras Racecourse to set up the baseline… because it was close to St Thomas Mount, which sat on the 13th parallel, the same latitude as Bangalore,” states the book. “Lambton was already familiar with the Bangalore region, which would be useful when he extended his triangulation from coast to coast, going from Madras to Bangalore and onwards to Mangalore along this latitude.”

There was no looking back from there. The surveyors would spend the next few decades establishing baselines and drawing triangles all across the country, even as the leadership baton was passed on from Lambton to Everest, Waugh and finally to Walker. “We know when it started, but not when it ended,” says Meera. “Very often, it is said that it lasted 70 years, because on-ground operations were going on for that long, but you still see reports written after 70 years. Even in the early 1900s, reports were coming out about the GTS because they were still doing calculations, still correcting things.”

What is clear, however, is the impressive legacy that the GTS has left behind, still lingering two centuries later. For instance, all Government-made maps of India, since the 1830s, have been based on one of the outcomes of this survey, the Everest Spheroid, which “best represents what the surface of the Earth is actually like in the Indian subcontinent,” according to the book. It is also useful for people trying to understand the Earth’s tectonic shifts. “Because the GTS benchmarks and baselines were made and measured with such accuracy, they provide useful points to geologists who study earthquakes and plate tectonics,” it further states.

Writing a book about the GTS

When Shruthi went on a holiday to Mussoorie in 2014, she visited George Everest’s house, located in Hathipaon. “I did some research and heard about the Great Trigonometric Survey for the first time,” she says. She found herself wanting to write about this house, which was “at that time, completely dilapidated”, and went on to publish an article about it in a national media outlet. As part of her research, she read The Great Arc by the British historian and journalist John Keay, a book about the survey, and found herself becoming increasingly fascinated by the GTS. “It has been running in my head since that time, and I wanted to write it for children,” she says. When she started researching for the book online, she discovered that Meera’s byline recurred in many of the articles about the same survey, she says. “First, I thought I would ask her for help with research; then, I ended up asking her to co-author the book with me, and she agreed,” explains Shruthi.

Rennel Grey’s map of Hindoostan before the survey

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Meera, who was directly involved in restoring an observatory located at the end of a baseline in Kannur, off the Hennur-Bagalur Road in Bengaluru, a structure that had been used to map the landscape, says that she first laid her eyes on “this really strange building” back in 2010. She began reading about the GTS “to figure out what this structure was,” she says, adding that INTACH started working on restoring it in 2018 or 2019. And while, unfortunately, the structure was later demolished in June 2024, “that was when my interest really took off,” says Meera, who spent a lot of time in various archives researching the survey.

Since the book is aimed at younger readers, the authors made sure that it was as conversational and simple as possible, says Shruthi. “I give a lot of context, see that it relates to real-life situations and make sure that we not only describe trigonometry and the mathematical part of it, but also offer a bird’s eye view,” she says. “We also put in activities for children to help them get a feel of things.” And it isn’t just children who are buying the book; adults seem to be enjoying it too. “I think, compared to my other books for children, we are getting a lot of adult interest because very few people know about this,” says Shruthi. “But, they’re fascinated by the topic.”

India in Triangles is available online and at all major bookstores